Bronze Sculpture

I have always been in awe of the art of Ancient Egypt. The artists of the three main periods – Old, Middle and New Kingdom- were just the greatest masters! They understood and applied the secrets of balancing force, movement and direction in their work. Likewise, the artists representing Modernism, Amadeo Modigliani, Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, Jean Arp and others from that era have always fascinated me. However, my absolute favorite here is Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957). To me he is truly the first ‘modern’ sculptor while at the same time creating an immediate connection to pre-Ptolemaic Egyptian Art. I love the clarity and balance evident in his sculptures which, in my view, are only paralleled by the sculptors of the above mentioned periods. A standard not easy to match. But I wanted to give it a go and in the early 1990s, after moving to New Zealand, I produced this series of Bronze sculptures, inspired by both modernist and Ancient Egyptian sculpture.

In the mid-1980s, while still in living in Germany, Günther Mancke (1925-2020) was one of my teachers. Together with Joseph Beuys and Antonia Berning, Mancke had studied sculpture under Ewald Mataré at the Academy of Fine Arts in Düsseldorf. A co-founder of the artists village Weißenseifen near Bitburg, he was also a passionate bio-dynamic bee-keeper, who after many years of research into the nature of the honeybee colony, developed the Sunhive as an alternative hive system (also see https://www.naturalbeekeepingtrust.org/).

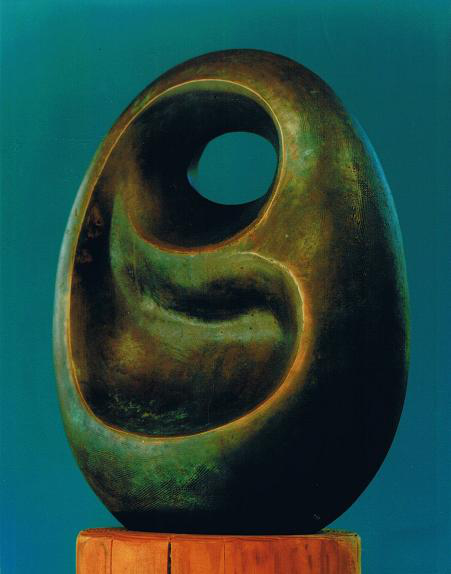

Under his tutelage I engaged in a study of metamorphosis, starting out with the sphere as an “ideal” shape. Working with clay, the idea was to basically retain the spherical shape, but still make changes to it. In the process I discovered that sculpture is really the result of ‘pressure’ exerted to any given material either from the inside, the outside or both. In the case of the sphere, the pressure from the outside is somewhat equal to the resistant force holding against from the inside, thus creating that balanced surface. If the pressure from the outside becomes stronger, the result will be an indentation, if the push is stronger from the inside, a bump will appear. My playing with the sphere resulted in the sculpture:

“The Birth of the Planet”, 3rd day of creation

According to the biblical creation story, on the third day God told the oceans to separate from the land. The water is represented by a wave with the land rising up as a mountainous shape, while the skies, represented by the star, are carrying the Earth.

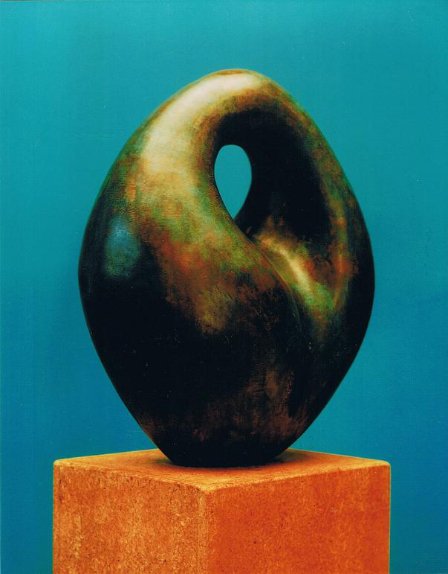

How could I now move from this sculptural shape to a completely different one but still retain certain elements? From the spherical shape I created an oval, egg-like shape, obviously by applying more pressure from the outside. The previously horizontal wave has been moved into an erect, vertical position and the initially mountainous shape is now a negative, open cavity.

“Untitled II”

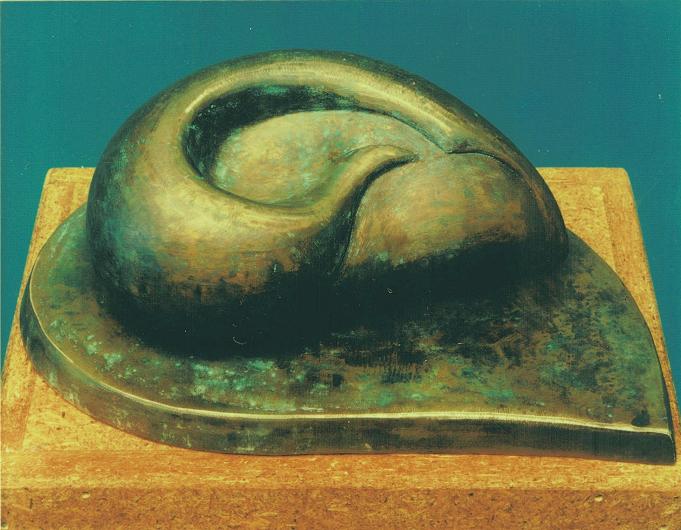

“Untitled III”, the third sculpture in this series, now features externally a diamond shape and the ‘wave’ is no longer just upright, but flowing through the opening at the top and down the other side. The separation into two individual parts at the bottom, which will appear in the work Pharao (see below), is already briefly indicated here.

“Untitled III”

In “Pharaoh”, the last work within the Metamorphosis Series, the opening has become so big that it just about equals the solid mass of the sculpture. Also, what was still ‘in one piece’ at the bottom of Untitled III is now split into two parts, with one ‘leg’ standing slightly behind the other. At this point in time I had a huge poster of the goldmask of Tut Anch Amun hanging on a wall in my bedroom. Probably, on a subconscious level, my Pharaoh is also a response to Tut Anch Amun in that it somehow represents the ceremonial wigs worn by the Kings of Egypt.

“Pharaoh”

Exploring the concept of Metamorphosis was exciting and rewarding – a bit like pondering the evolution of a butterfly which starts out from an egg and moves through I believe 12 different stages of existence until it is ready to spread its wings. The fact that all the stages are connected and actually build on each other is not immediately obvious. In my case, what started out as a spherical body went through different stages, many more than just these four. But the in-between stages were, more or less, variations of the theme. I wanted to execute just the significantly different ones that could stand as sculptures in their own right just like the other works from my Bronze series.

While the other pieces do more or less speak for themselves, there are a few words I would like to convey about the piece called:

“The Decapitation of the Magic Bird”, dedicated to Jaques Prévert

It has always greatly concerned me how educational systems, through their curricula, divert or even suppress any meaningful approach to life. Far too early are children forced into performance and conformity. I was myself bored stiff at school and certainly wanted something better for my children. No wonder the poem Page from a Notebook by French poet and screenwriter Jacques Prévert (1900-1977) greatly impressed me. Not only does it accurately describe that fateful classroom scenario, but it also gives hope: it gives us the “Magic Bird” as a symbol of creativity and freedom, forever roaming the skies inviting us to connect with the magic of all creation and existence.

While in my sculpture I am representing it as a skull on a platter, decapitated (a bit like the biblical Judith presents the head of Holofernes in various different paintings), what I really mean to say is: We can put flesh around that skull again! Just like the school kids in Prévert’s poem, we can see and hear that bird, listen to its song, follow its call and thus transform our reality. We can liberate ourselves from all that manipulation and imprisonment and have the walls of our super- or self-imposed prisons tumble down.

Page from a Notebook

by Jacques Prévert

Two and two make four. Four and four make eight. Eight and eight make sixteen…

Repeat! says the teacher. Two and two make four. Four and four make eight. Eight and eight make sixteen…

But there is the songbird passing by in the sky! The child sees it… The child hears it… The child calls it: Save me, play with me, bird! So the bird comes down and plays with the child.

Two and two four… Repeat! says the teacher. And the child plays and the bird plays with him.

Four and four make eight, eight and eight make sixteen. And what do sixteen and sixteen make? They don’t make anything, sixteen and sixteen and especially not thirty-two anyway. And they go away.

And the child has now hidden the bird in his desk. And all the children hear his song. And all the children hear the music.

And eight and eight also go away. And four and four and two and two also leave. And one and one make neither one nor two.

One and one go away too.

And the song bird plays. And the child sings. And the teacher yells: When will you stop acting like fools!

But all the other children listen to the music. And the walls of the classroom slowly crumble. And the windows become sand again.

The ink becomes water again.

The desks become trees again.

The chalk becomes a cliff again.

The inkwell again becomes a bird.