Working the Grid

My personal love affair with the Square and the Grid began on a very cold winter day in 2011/2012 while visiting Germany. The art historical context was, of course, well known to me and I had studied the works of many of those who had been infatuated with this concept before me – Malevich, Mondrian, Klee, Albers and many others. But I had never felt the urge to work along those lines myself. On that particular day, however, it hit me really hard: I got initiated and became part of the “square and grid-family”.

But before I tell my own story, let us briefly explore the Square or Grid in Art as it plays such an important role in the history of painting. It was initially used as a working tool when transposing original designs onto canvases. The invention of this technique is often attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, but at the same time Albrecht Dürer was also applying it. The process was as follows: for a painting to be produced, an exact drawing would be made, which was then overlaid with a grid of squares or oblongs. A grid of similar size or proportion was subsequently drawn onto the blank canvas. Square by square the painting would then be transferred from the drawing onto the canvas. The drawings were usually safeguarded and well looked after so that if copies were required, as was often the case, these could be reproduced straight from the drawing rather than the original painting. We can safely assume that most academically executed paintings do have an underlying grid which was subsequently painted over.

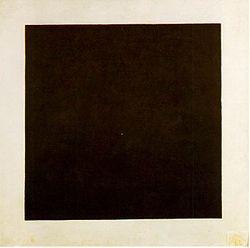

The 20th and 21st centuries saw this grid transmute from an initial tool to become itself a theme in art. Today, the square represents one of the paradigms of modern art. Uncounted artists have engaged with it in form and concept and there is a multitude of painterly and sculptural concepts dealing with the square. While, for example, some of Matisse’s works show traces of grids visibly integrated into the paintings, it was Kazimir Malevich, one of the founders of Russian Suprematism, who chose the square as one of his most frequently used themes. His painting Black Square on White Background (1915) was truly revolutionary.

Kazimir Malewich, Black Square on White Background, 1915

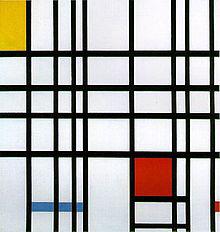

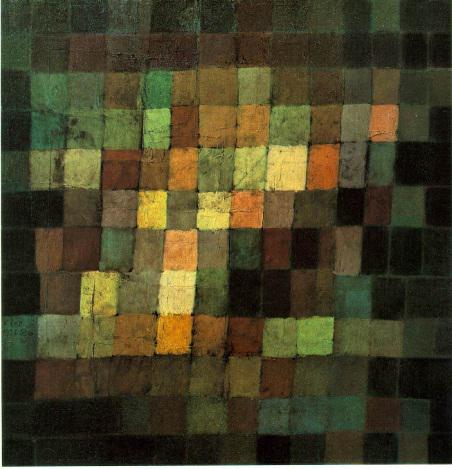

Works by Malevich and especially also El Lissitzky, which were exhibited in Germany, strongly influenced the Dutch group De Stijl, founded in 1917 (Theo van Doesburg, Vantongerloo, Mondrian, and others) as well the German art school Bauhaus, in particular Paul Klee and Josef Albers.

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Yellow, Blue and Red, 1937-1942

Paul Klee, Ancient Sound, 1925

In the 1950s, Bauhaus teacher Josef Albers, who had immigrated to the USA, began work on his famous Homage to the Square Series. This would be executed over a period of 25 years and resulted in more than 1000 works, including paintings, drawings, prints and tapestries. A vast collection of his works can be viewed at the Josef Albers Museum Quadrat in Bottrop, a building which in itself is homage to the square.

Museum Quadrat in Bottrop

Josef Albers, Homage to the Square, 1965

The collection of Marli Hoppe–Ritter in Waldenbuch near Stuttgart/Germany can certainly also be seen as a tribute to the square. This most interesting collection comprises approximately 800 paintings, objects, sculptures and graphic works. “It unites many artistic concepts that have the square as a point of departure or goal and thus covers in concentrated form a whole century of art history. The breadth of painterly and sculptural confrontation with the square, its continuing dynamism as a form and the exciting lines that can be drawn across through 20th and 21st-century art, show how compelling the Collection’s concept is. Choosing a small history of the square as a collection concept has proven to be exciting, surprising and of special artistic interest. It is by no means boring, but rather an endless, generous stream of artworks that have to do with the serious, playful, mathematic, spiritual, analytical and humorous aspects of the “four corners with right angles.” (cited from www.museum-ritter.de/sammlung).

And now to cut my own long story short. It was freezing cold on that particular day in Wasserburg, the temperatures had fallen to minus 20 degrees. But nevertheless, I went for a stroll along the shores of Lake Constance. The water was frozen over with lots of cracks in the ice forming amazing shapes – also grids and squares – while the rays of the sun were creating the most beautiful prisms of light and colour on the ice sheets. I was completely captivated and in awe.

Well, believe you me, from that day on, for a very long time, I saw squares and grids absolutely EVERYWHERE, also in the stones piled up below the church, which was not too difficult.

Over the following decade and up until now those impressions have formed the basis of a large body of work, as for example the different ‘Prayer Flags Series’. These are based on the Buddhist, Himalayan tradition of stringing bands of colourful square or rectangular pieces of cloth along mountain ridges or tying them to sacred places. Traditionally these flags were imprinted with images, sacred texts and blessings. Himalayans believe that the wind blowing these messages across the land brings healing and good fortune. When the prints deteriorate, the prayers become part of the universe. Well, plenty of good, positive thoughts in my work, too.

The following series should also be understood as part of the Prayer Flags theme. ‘Squares, Lines and Planes’ are probably mostly Bauhaus inspired, while the ‘Skies’ works are based on my frequent observation of rather sharp-cornered geometric real-life cloud formations appearing in the sky. Clouds are by no means generally fluffy or round at the edges. The tension within these 4-part-formations appears to be the greatest immediately before it is about to disintegrate. My focus was on capturing exactly this moment.

In the “Strings Attached” series I used black wool to separate the coloured areas from each other and create that clearly visible grid.

Even if no longer obviously featured, this grid is still present in “And in the End there is only the Line”. This concept leaves so much beautiful room to explore even just one colour in a minimalist way while still allowing for some structural statement within the painting.

“Square of Nine” represents a rather different approach. This piece is made up of 9 square individual canvases, 30cm x 30cm. My choice of colour here was also a bit outside of my normal colour scheme as I mostly use primary/ complementary but definitely bright colours and shades. At this point in time I had been working the grid non-stop for about 5 years and was so deeply in its grip that I felt the need to consciously break out. I could not. It was so frustratingly difficult. Every painting I started, with the best intentions of doing something different, still ended up being somehow linked to this theme. Until one early summer morning in 2016 when I stepped out onto the veranda of my house that is…

Swallows had built a nest in the rafters and were peacefully doing what they had to do, usually unbothered by my presence and mostly ignoring me. Not on that day. What seemed like an army of birds – remember that Hitchcock movie?? – was diving at me up and down, back and forth, completely out of the blue. It took a few moments for me to understand what was going on: the babies had hatched. They were now sitting on the clothes line while the parents, and probably some aunties and uncles, were on more than high alert. I observed and took in their erratic behaviour and the way they clearly tried to attack. My next thought was: now I know how to get out of that grid work… and this resulted in my “Flight of the Swallows” Series.

While I love those erratic, swirly patterns, which are great fun to do, I am continuing to work the grid, which I am sure will be an ever re-occurring concept for me to engage in.